The History Of The Five Points: The Notorious New York Neighbourhood & Its Violent And Rich…

There are parallels of how Bombay is the New York of India and how in a rather grotesquely uncanny resemblance, how New York is the Bombay…

There are parallels of how Bombay is the New York of India and how in a rather grotesquely uncanny resemblance, how New York is the Bombay of America.

Home to the highest population a city can hold in each country, cities where millions flock to on a regular basis in search of work, hope, fame, and freedom, where housing prices continue to increase on a periodical basis, cities on the banks of the sea and home to the mighty stock exchanges of Dalal Street and Wall Street; stark symbols of the wealth and power both cities can offer, adrift with skyscrapers, taxis, and traffic, while on the other side of the coin, the home of the poorest, most busy and bustling yet troubled streets each country calls their own.

New York has a deep and violent history which many people, in today’s times at least, don’t realize, or, are unaware of, nothing more so typified than by the notorious Five Points neighborhood of New York City in the 19th and early 20th century.

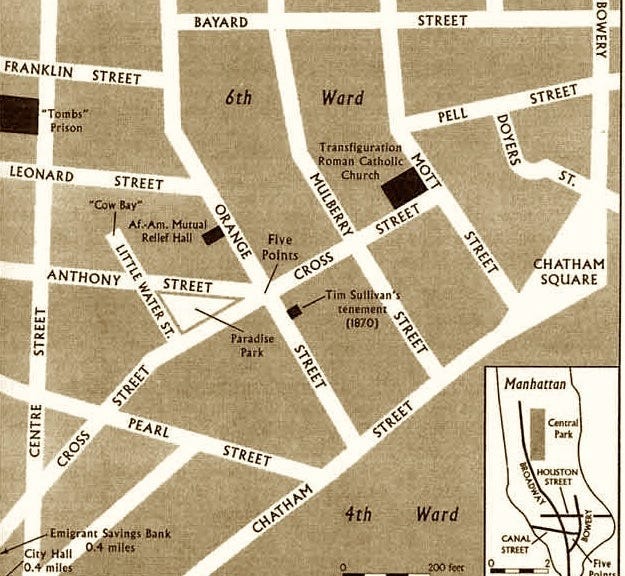

The Location Of Five Points

In the 19th century, the Five Points was bound by Centre Street to the west, the Bowery to the east, Canal Street to the north, and Park Row to the south(near modern-day Chinatown).

Or as other accounts suggest, “The name Five Points was derived from the five-pointed intersection created by Orange Street (now Baxter Street) and Cross Street (now Mosco Street); from this intersection Anthony Street (now Worth Street) began and ran in a northwest direction, creating a triangular-shaped block thus the fifth “point”. To the west of this “point” ran Little Water Street (which no longer exists) north to south, creating a triangular plot which would become known as Paradise Square or Paradise Park.”

The neighbourhood was widely regarded as the biggest slum of New York(similar to Dharavi in Bombay) known for its notoriety, filth, crime, and vice.

According to accounts, at that particular time, the Five Points was commonly regarded as one of the worst disease-ridden slums in the Western World. In fact, when it came to population density, illness, infant mortality, unemployment, prostitution, violent crime, etc., The Five points was only rivaled by certain areas of London’s East End.

The emerging confluence of African, Irish, Anglo, and, later, Italian and Jewish immigrants and culture, seen first in the Five Points, would be an important leavening in the growth of the United States, while the area was considered a rich melting pot of early America at the time.

Accounts of Five Points: From Dickens To Sante

“Ascend these pitch-dark stairs, heedful of a false footing on the trembling boards, and grope your way with me into this wolfish den, where neither ray of light nor breath of air, appears to come….”

“Here too are lanes and alleys, paved with mud knee-deep, underground chambers, where they dance and game; the walls bedecked with rough designs of ships, and forts, and flags, and American eagles out of number: ruined houses, open to the street, whence, through wide gaps in the walls, other ruins loom upon the eye, as though the world of vice and misery had nothing else to show: hideous tenements which take their name from robbery and murder: all that is loathsome, drooping, and decayed is here,” wrote Charles Dickens about the Five Points on his highly celebrated visit to America.

Dickens insisted on visiting the Five Points on his stop in New York during his tour of America and because of its mythical status in the world at the time, Dickens made it paramount that he visited the neighbourhood.

Dickens’ account of the Five Points and America in 1842 was one of the earliest written accounts of America that was available for Europeans to read during the 19th century.

“Every day’s experience gives us increased assurance of the safety of the temperate and prudent, who are in circumstances of comfort…. The disease is now, more than before rioting in the haunts of infamy and pollution. A prostitute at 62 Mott Street, who was decking herself before the glass at 1 o’clock yesterday, was carried away in a hearse at half-past three o’clock. The broken-down constitutions of these miserable creatures, perish almost instantly on the attack…. But the business part of our population, in general, appear to be in perfect health and security.” — ” New-York Mercury, 18 July 1832″

The Irish and other immigrants began to group together to form gangs as a means of status, sustenance, and livelihood which formed the core of what made the Five Points so notorious.

In Low Life, a 1991 study of New York’s many overlapping 19th-century underworlds, journalist Luc Sante reports, “The basic unit of social life among young males in New York in the nineteenth century was (as it perhaps is still and evermore shall be) the gang.” For “the Manhattan of the immigrants,” he says, the gang served as “an important marker, a sort of social stake driven in,” which allowed various ethnic groups to control a few blocks of a city in which they wielded very little real power. “They engaged in violence,” writes Sante, “but violence was a normal part of life in their always-contested environment; turf war was a condition of the neighborhood.”

The Real Gangs Of New York

1. The Forty Thieves

One of Gotham’s earliest known criminal outfits, the Forty Thieves operated between the 1820s and 1850s in the Five Points neighborhood of Manhattan. This band of Irish thugs, pickpockets, and ne’er-do-wells first came together in a grocery store and dive bar owned by a woman named Rosanna Peers. Under the leadership of Edward Coleman — a notorious rogue who was later hanged for beating his wife to death — what started as a motley group of petty criminals soon blossomed into a feared street gang with its own rules and organizational structure. Members of the Forty Thieves reportedly had quotas that required them to steal a certain amount of goods each day or face expulsion. What’s more, the gang even franchised itself in the form of the “Forty Little Thieves,” a collection of juvenile apprentices who served as pickpockets and lookouts.

2. The Bowery Boys

One of the most storied gangs of New York, the Bowery Boys were a band of lower Manhattan toughs who clashed with the Irish Five Points gangs during the 1840s, 50s, and 60s. Unlike some of their criminal counterparts, most of the Bowery Boys dressed in elegant clothing and held legitimate employment as printers, mechanics, and other apprentice tradesmen. But when they weren’t on the job, these young hoodlums haunted the saloons and back alleys of the Bowery and engaged in bloody turf wars with rival gangs like the Dead Rabbits.

The Bowery Boys often acted more as a political club than a mob, and many of their brawls were with supporters of rival politicians. The gang would sometimes even station its members at polling places to intimidate voters into supporting a particular candidate. In return, the gang’s home district would receive money and preferential treatment once the politician was in office.

3. The Dead Rabbits

This crew of Irish immigrants was one of the most feared gangs to emerge from the Five Points, so named for its location at the intersection of five crooked, narrow, downtown streets. For more than 60 years, the Five Points (near modern-day Chinatown) was one of the city’s most notorious — and dangerous–neighborhoods. Throughout the 1850s, the Dead Rabbits excelled at robbery, pick-pocketing, and brawling — particularly with their sworn enemies, the Bowery Boys. The group was made up mostly of young men, but it wasn’t unheard of for women to join in on the violence. According to legend, one of the most feared Dead Rabbits was “Hell-Cat Maggie,” a woman who reportedly filed her teeth to points and wore brass fingernails into battle. While the Rabbits mostly dabbled in petty crime, they were also famous for the events of July 4, 1857, when one of their street fights with the Bowery Boys turned into a bloody riot that killed a dozen people.

The Dead Rabbits supposedly began as an offshoot of another gang called the Roach Guards, but some historians have suggested the two were actually one and the same. In fact, one popular theory argues that the term “dead rabbit” was simply a pejorative used by the Bowery Boys and the New York press in reference to members of the Roach Guards and other Five Points gangs.

4. The Daybreak Boys

New York’s 19th-century gang activity wasn’t limited to the rough and tumble streets of Manhattan — it also extended into the waters of the East River. The Daybreak Boys were one of the most ruthless crews of “river pirates” who preyed on the city’s booming shipping industry during the late 1840s and 1850s. As their name suggests, the Daybreakers — whose leaders went by such colorful monikers as Cow-legged Sam McCarthy and Slobbery Jim — preferred to strike in the hours before dawn. Using small rowboats, these juvenile gangsters would silently row their way alongside anchored shipping vessels. Sneaking aboard, they would steal as much cargo as they could before returning to their dinghies and escaping to a rendezvous point at a gin mill in the Fourth Ward.

To prove their mettle, prospective members were reportedly required to have already killed at least once before joining the group, and the Daybreak Boys were supposedly responsible for more than 30 murders — it wasn’t unusual for an unlucky watchman to end up with a slit throat or a fractured skull during one of their robberies. The gang reportedly fell apart in the late 1850s after a police crackdown, but not before they had claimed thousands of dollars in booty.

5. The Whyos

Formed from the remnants of several defunct Five Points outfits, the Whyos were one of the most dominant New York street gangs from the 1860s to the 1890s. The group started out as a loose collection of petty thugs, pickpockets, and murderers, but by the 1880s they had graduated to more high-class crime like counterfeiting, prostitution, and racketeering. As their grip on Manhattan tightened, many of the gang even opened legitimate side businesses such as casinos and saloons.

They may have masqueraded as upstanding citizens, but the Whyos were still notoriously tough customers. One hood by the name of “Dandy” Johnny Dolan supposedly carried a copper eye gouger and wore shoes outfitted with axe blades. Another Whyo called Piker Ryan was once caught with a detailed price list of all the gruesome deeds he could be hired to perform. A simple punch to the face was only two bucks, chewing off an ear cost $15, and a murder — which Ryan’s catalogue described as “doing the big job” — went for the princely sum of $100.

6. The Five Points Gang

This legendary mob came together in the 1890s, when the Italian gangster Paul Kelly united the remaining members of the Dead Rabbits, Whyos, and other Five Points gangs under his own banner. From his headquarters in the New Brighton Dance Hall, Kelly marshaled an army of 1,500 thugs in bloody turf wars with his archrivals, a Jewish gang run by the famed hood Monk Eastman. The two groups engaged in constant brawls and once even squared off in a massive gun battle under the Second Avenue elevated train line.

When they weren’t participating in Wild West-style shootouts, the Five Pointers ran widespread robbery, racketeering, and prostitution rings. They also dabbled in legitimate front businesses and worked as strong-arm men for the corrupt Tammany Hall political machine. The gang’s influence eventually waned in the 1910s, but not before they had helped train the next generation of mob bosses. Among others, the Five Pointers initiated thugs like Al Capone, Lucky Luciano, and Johnny Torrio into a life of organized crime.

7. The Eastman Gang or Eastman Coin Collectors

Led by the Jewish mobster Edward “Monk” Eastman, the Eastman Gang rose to become one of New York’s most feared criminal organizations in the 1890s. As the kings of Manhattan’s Lower East Side, the 1,200 “Eastmans” raked in huge profits running brothels, protection rackets, drug rings, and even murder-for-hire operations. Like their rivals in the Five Points Gang, Eastman’s boys also teamed with corrupt politicians in voter fraud. In return, the city’s crooked lawmakers turned a blind eye to the gang’s illicit activities.

A career criminal, Monk Eastman delighted in violence and was known to personally dish out beatings to his enemies. This hands-on approach proved to be his undoing in 1904, when he was arrested and jailed for a simple street mugging. With their leader behind bars, the Eastmans splintered into several smaller, less powerful factions in the 1910s. Monk Eastman later enlisted in the armed forces and forged a legendary reputation fighting in the trenches of World War I. But while he returned to New York a war hero, the former gang boss’s old life ultimately caught up with him, and he was brutally gunned down on a city sidewalk in 1920.

The Rise Of The Italian-American & Jewish Mafia

By the 1870s a new wave of now Italian and Eastern European Jewish immigrants were settling into the area. Criminal gangs of Irish, Jewish, and Italian criminals began competing for control of the territory, rackets, and revenue to be made from illicit activities. Monk Eastman’s Eastman Coin Collectors originally had many Irish members

In comparison with the tribal mayhem of the mid-19th century, the Italian-American mafia, as it rose to power in the 1890s, was positively corporate in its structure, built on complex hierarchies and entrepreneurial sophistication. But the mafiosi were not the only outlaws demonstrating a head for business. When a bruiser named Piker Ryan, a member of the fearsome Whyos gang, was arrested by the police in the late 1800s, he was found to be carrying a presumably market-tested price list of crimes-for-hire, including:

Punching. . . $2

Both eyes blacked. . . $4

Ear chawed off. . . $15

Stab. . . $25

Doing the big job. . . $100 and up

It was within the dwellings of the Five Points that the Chicago outfit of Al Capone, Johnny Torrio, and Lucky Luciano had their roots. Torrio, Capone, and Luciano ran the racket and were raised in the streets of the Five Points. Conspiring with fellow New York gangsters namely the Jewish mob of mastermind Arnold Rothstein and Meyer Lansky, the history of Five Points took its next turn where the gangsters began more organised rackets well into the prohibition years, recounted brilliantly on the HBO TV show ‘Boardwalk Empire’.

The Film ‘Gangs Of New York’ by Martin Scorsese

However, Martin Scorsese’s film ‘Gangs Of New York’ was set back in the mid 19th century based on the immigrants and turf wars of gangs in that era.

An excerpt from a film review of the movie reads…

“When he was growing up on Lower Manhattan’s Elizabeth Street in the 1950s, Martin Scorsese noticed tantalising vestiges of a New York City that simply didn’t fit into the Little Italy neighbourhood he otherwise knew so well. There were the tombstones dating to the 1810s in the graveyard at nearby St. Patrick’s church, cobblestone pavements that hinted at horse-drawn traffic, and the “very tiny, very ancient” basements he discovered beneath late-19th-century tenements. “I gradually realised that the Italian-Americans weren’t the first ones there, that other people had preceded us,” says Scorsese. “This fascinated me. I kept wondering, how did New York look? What were the people like? How did they walk, eat, work, dress?”

“That childhood obsession with a vanished past propels the Gangs of New York, Scorsese’s epic evocation of the city’s brutal, colourful underworld in the first half of the 19th century. But the director says the movie, had its genesis in a “chance encounter” more than 30 years ago. In January 1970, Scorsese, by then an aspiring filmmaker, stumbled across a volume in a friend’s library that changed everything he thought he knew about his old neighbourhood. Suddenly, the nameless ghosts that had flitted through those mysterious basements sprang to life. The book was The Gangs of New York, an account of the city’s 19th-century underworld published in 1927 by journalist Herbert Asbury. “It was a revelation,” Scorsese says. “There were so many gangs!”

“In Asbury’s vivid chronicle, Scorsese discovered a deadly subculture of hoodlums with names like the Bowery Boys, the Plug Uglies, the Short Tails, and the Dead Rabbits, the latter so-called, it was said because they carried a dead rabbit on a pike as their battle standard. In these pages, he was introduced to legions of once-notorious gangsters, among them Bill “the Butcher” Poole, Red Rocks Farrell, Slobbery Jim, Sow Madden, Piggy Noles, Suds Merrick, Cowlegged Sam McCarthy, Eat ’Em Up Jack McManus. Not all the thugs, he discovered, were male. Hell-Cat Maggie, legend has it, filed her front teeth to points and wore artificial brass fingernails, the better to lacerate her adversaries.”

“Behind much of the violence lay a clash that involved, on the one hand, a population of largely protestant Americans, some of them with 18th-century English and Dutch roots in the New World, some of them, more recent arrivals. This group collectively came to be known as nativists, for their perceived entitlement to native American soil. They squared off against Catholic Irish immigrants who arrived in the millions during the 19th century. Nativists “looked at the Irish coming off the boats,” Scorsese adds, “and said, ‘What are you doing here?’ It was chaos, tribal chaos.”

“In Asbury’s book, Scorsese recognized something larger than a portrait of the city’s bygone lowlife. As the descendant of immigrants himself (his grandparents arrived from Sicily at the turn of the century), he saw in the bloody street fighting of the mid-19th century a battle for nothing less than democracy itself. “The country was up for grabs, and New York was a powder keg,” says Scorsese. “This was the America not of the West with its wide open spaces, but of claustrophobia, where everyone was crushed together. If democracy didn’t happen in New York, it wasn’t going to happen anywhere.”

“Beginning with a bloody gang war in 1846, Gangs of New York culminates amid the Götterdämmerung of the 1863 draft riots, in which perhaps as many as 70,000 men and women, aroused by the introduction of mandatory conscription during the third year of the Civil War, rampaged through the streets of New York, setting houses afire, battling police and lynching African-Americans. Federal troops had to be brought in to quell the disturbance.”

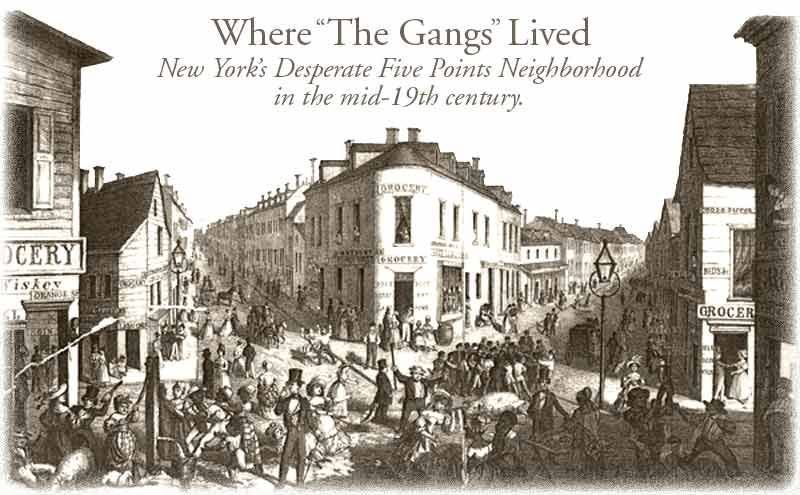

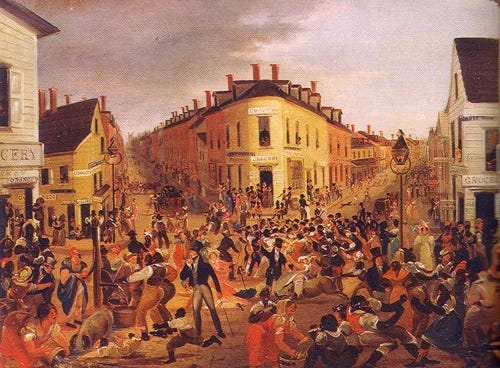

“Most of the film’s action takes place around the seething Five Points slum, then a paramount symbol of anarchy, violence, and urban hopelessness. About 1830, the New York Mirror described the area as a “loathsome den of murderers, thieves, abandoned women, ruined children, filth, drunkenness, and broils [brawls].” Around the same time, George Catlin, the artist best known for his portraits of Indians on the Great Plains (see “George Catlin’s Obsession,” p. 70), painted the Five Points district, depicting a riotous scene of brawling drunks, leering prostitutes and intermingled races.”

“To most Americans, the very name itself suggested unspeakable wickedness and sin. Individual tenements acquired monikers like the Gates of Hell or BrickbatMansion. The most notorious hellhole of all, and a key setting for the film, was a cavernous abandoned brewery turned tenement. Here, a population of several hundred, the poorest of Irish immigrants and African-Americans, lived under unspeakable conditions.”

“Prostitutes plied their trade openly in a single vast chamber, known as the Den of Thieves. Beneath the basement’s earthen floor, the dead, too destitute even for a proper burial, were sometimes interred. Everywhere in the neighborhood, lanes ran thick with a soup of rotting garbage and human waste; pigs and other animals foraged in the fetid byways. “Saturate your handkerchief with camphor, so that you can endure the horrid stench,” visitors were advised by one 19th-century temperance worker.”

“Although nearly every trace of the world that Scorsese has re-created has long since been obliterated, there are a few exceptions. At 42 Bowery, an address claimed by some to be the former clubhouse of the Bowery Boys, a Chinese restaurant now stands. Several blocks of Bayard Street, where the Bowery Boys and the Dead Rabbits brawled in the 1850s, remain much the same. In Five Points, which includes a section of modern Chinatown, small children clamber over jungle gyms in a public park. If the ghosts of the thugs and mayhem artists, the murderers and pickpockets, the embattled nativists and desperate immigrants still linger, their murmurings are lost among the voices of today’s New Yorkers, chattering to each other in half a dozen dialects of Chinese, in Haitian, French, Spanish.”

In this video, the movie is examined for its historical accuracy:

The culminating ending scene of the movie is a very moving and relevant one. In the movie, the ending scene depicts the graves of both protagonists Bill ‘The Butcher’ Cutting and ‘Amsterdam’, in a time-lapse, as grass, mud, plants, and trees grow over their graves while in the background, across the waterline, the skyscrapers and technology of the future are depicted as slowly emerging from the 19th-century architecture, replacing the city’s skyline with the 21st-century architecture of today, as the time-lapse continues.

It’s a hard-hitting reminder that despite the rich history a place holds at a particular period of time, and the past it was conceived in, the battles fought and won, and the blood once spilled over the land, all slowly fade and are ultimately lost & overlooked or forgotten in time.

However, the myth, legend, folklore, and culture of a bygone time of an iconic city and a key component in the history of modern America, remain in remnants in the form of stories and art, which last and linger on to this day.

It’s unbelievable, if you just sit back and think about it, of how something as commonplace as a neighbourhood, can bear so much history, legend, and violence and which undoubtedly makes it the most interesting neighbourhood that was ever conceived.

This is the story of the Five Points.

This article contains excerpts from: history.com, smithsonianmag.com, and others