Moanin’ At Midnight: The Story Of Howlin’ Wolf — One Of The Greatest Blues Musicians Of His Time

“I was broke when I was born, that’s the reason I’m howlin!” — Howlin’ Wolf (Chester Burnett)

“I was broke when I was born, that’s the reason I’m howlin!” — Howlin’ Wolf (Chester Burnett)

Few stories of musicians are as troubled and tragic as the story of the early life of Chester Burnett better known by his stage name ‘Howlin’ Wolf’.

Wolf would go on to become a blues great in his later years but his beginnings were forged firmly in tragedy and abuse.

Born to Leon “Dock” Burnett and Gertrude Jones on June 10, 1910, in White Station, Mississippi, a tiny railroad stop between Aberdeen and West Point in the Mississippi hill country, many miles away from the Delta, Burnett gravitated to music in his early years, which was his only solace in a life of physical abuse, tragedy and strife.

Fascinated by the emerging music at the time as a boy, he would often beat on pans with a stick and imitate the whistle of the railroad trains that ran nearby. He also sang in the choir at the White Station Baptist church, where Will Young, his stern, unforgiving great-uncle preached.

When his parents separated, his father moved to the Delta, and his mother left Chester with his uncle Will, who mistreated and physically abused him constantly. One childhood friend said Will Young was “the meanest man between here and hell.”

Wolf’s relationship with his estranged mother was also troubled. Gertrude spent much of her adult life as a street singer, making a living by selling hand-written gospel songs for pennies. She disowned her son Chester, claiming he played “the Devil’s music.” and Wolf’s wariness can be traced to his bleak childhood.

Wolf was forced to walk many miles and go live with his great uncle Will who was a violent, cruel man who mistreated all the children under his and his wife’s care, and systematically physically/psychologically abused the young Wolf in particular — until age thirteen when he ran away to avoid an especially brutal beating for inadvertently killing a hog.

Wolf “hoboed” his way on train and foot to the Mississippi Delta after running away from his uncle’s residence to live with his father and new family, who were farmers on a plantation as a sharecropper which involved toiling in the fields for several hours a day and Wolf continued the trade well into the 1940s.

Chester became fascinated by local blues musicians, especially the Delta’s first great blues star, Charley Patton, who lived on the nearby Dockery Plantation.

When his father bought him his first guitar in January 1928, he convinced Patton to give him guitar lessons. He later took impromptu harmonica lessons from Sonny Boy Williamson II (Rice Miller), who was romancing his step-sister, Mary. He learned to sing by listening to records by his idols “Blind” Lemon Jefferson, Tommy Johnson, the Mississippi Sheiks, Jimmie “the Singing Brakeman” Rodgers, Leroy Carr, Lonnie Johnson, Tampa Red, and Blind Blake.

For awhile, he played music while wearing tiny wire-rim glasses and a dark suit like the only known photo of Lemon Jefferson. And when he wasn’t working on his father’s farm, he traveled the Delta with other musicians such as Sonnyboy Williamson, Robert Johnson, Patton, Son House, and Willie Brown.

As recounted by NPR in their piece about Howlin’ Wolf, Burnett continued to toil and labour in the fields and plantations as a sharecropper until he finally got his big break:

When your father has worked a good piece of bottomland into producing crops that support the family and he dies young, if you’re the oldest son you have to take over, no matter what. That’s one theory of why Chester Arthur Burnett didn’t make his first recording until he was 41. Other bits of the story, which are still falling into place, have him learning music from Charley Patton, maybe spending some time in prison and having a bad time in the Army during the war.

But by 1951, the farm was in safe hands, and Burnett, performing on the radio as Howlin’ Wolf, caught the ear of Sam Phillips, who was running the Memphis Recording Service and talent-scouting for blues labels like Chess and Modern.

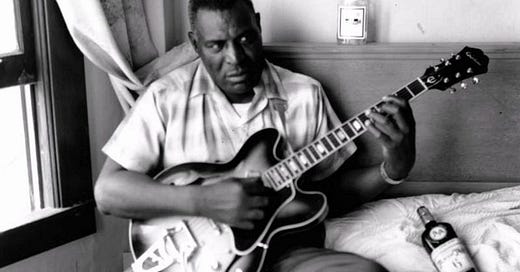

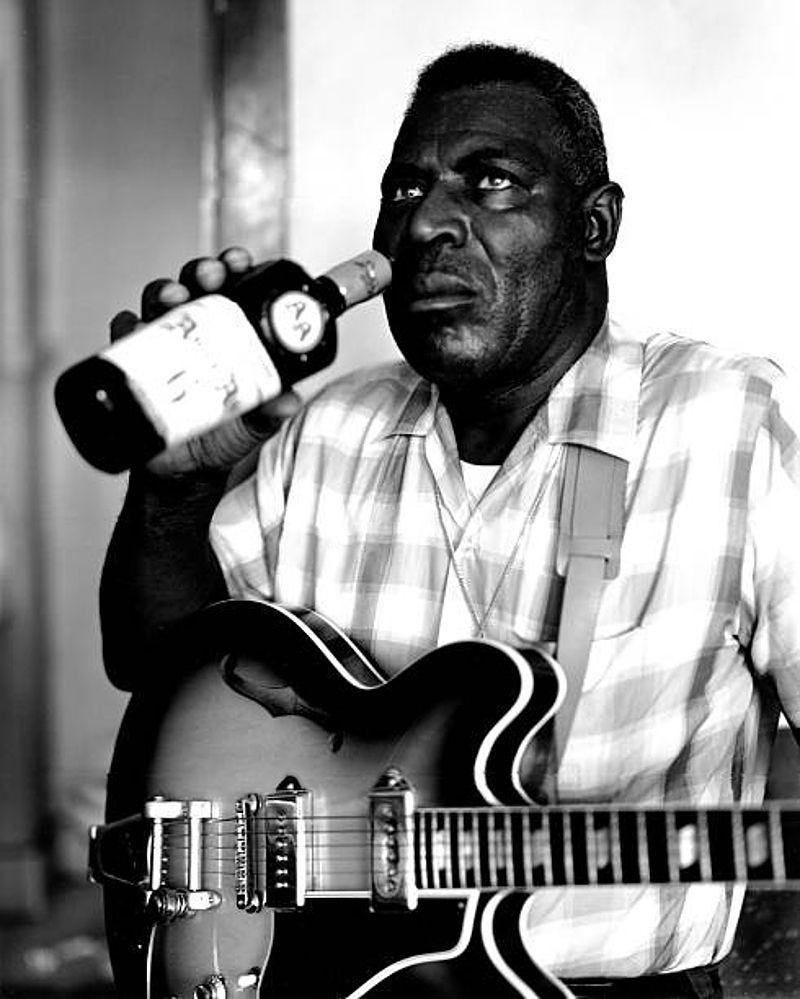

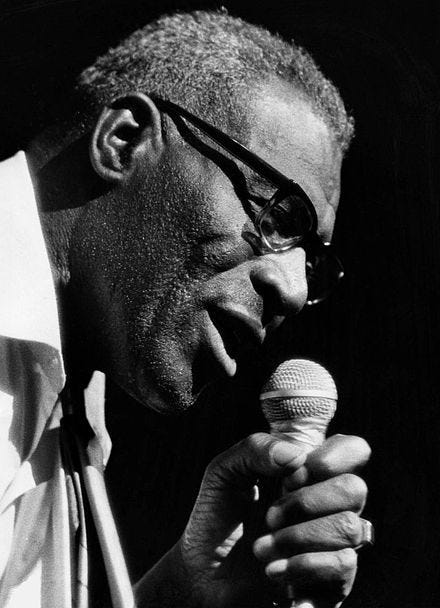

Standing at 6 ft 3" and weighing 275 lbs, Wolf was as larger than life as his stature.

From the start, Wolf’s voice was startling — huge and raw like Charlie Patton’s, and even more powerful. He learned to play guitar and blues harp simultaneously, using a rack-mounted harp.

John Shines, who also traveled with Robert Johnson, said, “I was afraid of the Wolf, like you would be of some wild animal….It was the SOUND he was giving off!”

Drafted in 1941, Wolf went into the Army Signal Corps and spent his time in the service mostly in the Pacific Northwest at Fort Lewis, Washington and Camp Adair, Oregon. He suffered a nervous breakdown in 1943 and was discharged from the Army, and soon moved with his girlfriend to a house in Lebanon, Tennessee.

As written on Vivascene, Wolf’s tenure in the army would expose the fragile nature of the gentle giant:

Though Wolf did not serve overseas in World War II, those four years in the army and especially the reasons for his discharge, are telling of the fragile inner nature within the tough giant, the permanent scars of his wounded childhood. Wolf suffered a nervous breakdown in the army, partly due to his inability to mesh into the soul/mind-crushing military machine, and his already nervous disposition towards all things rooted in authority and control due to the abuse suffered as a child at the hands of his stepfather. Labelled a “mental defective” by one army psychologist, neatly wrapping up any loose ends for the military cause and effect side, Wolf was honorably discharged back into society where he could resume his ‘intelligent’ musical rambles.

After his girlfriend succumbed to mental illness, Wolf left Tennessee and returned to playing music, and helping his father on his farm during the spring and fall. The rest of the year, Wolf was traveling through the South, playing with Delta bluesmen such as Willie Brown and Son House.

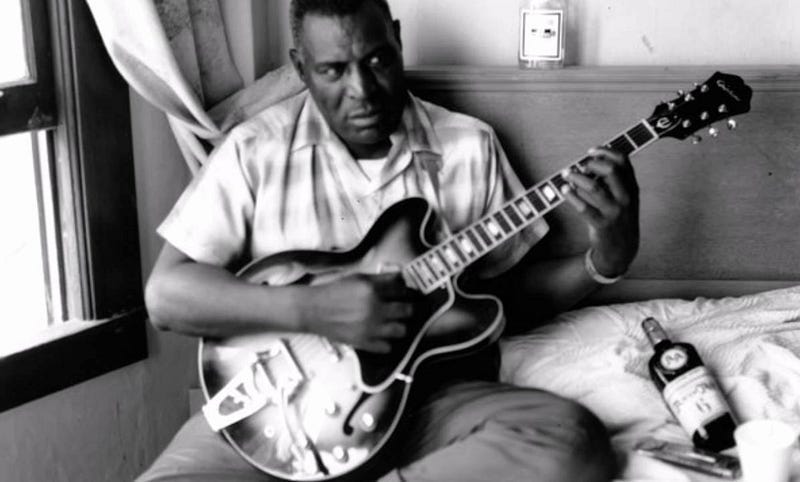

In 1948, Wolf moved to West Memphis, Arkansas, where he put together a band that included harmonica players James Cotton and Junior Parker and guitarists Pat Hare, Matt “Guitar” Murphy, and Willie Johnson. He also got a spot on radio station KWEM, playing blues and endorsing farm gear.

Wolf’s big break came in 1951 when he was noticed by legendary Memphis record producer Sam Phillips who was young at the time scouting artists for various labels.

It was Phillips, who took him into the studio and recorded “Moanin’ at Midnight” and “How Many More Years,” and leased them to Chess Records. Released in 1952, they made it to the top 10 on Billboard’s R&B charts. Wolf cut other songs that Phillips let out both to Chess and RPM. Chess eventually won the fight for Wolf, and he then moved to Chicago in 1953 and called the city home for the rest of his life.

Phillips, who was exceptionally adept at recognizing musical talent later discovered Elvis Presley, Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis, Johnny Cash, and Charlie Rich.

However, he would regret losing the rights to Wolf to Chess records and even went on record to admit that Wolf was his greatest discovery and losing Wolf to Chicago was his biggest career disappointment.

“Chester Burnett had such a soulful sound that even though his words were always good blues words, that man didn’t have to say a sound. Just like his song ‘Moanin’ at Midnight.’…When it came out, it was as if everything just stopped, everything that was going on. Time stopped. Everything stopped. And you heard the Wolf.”

“Had the young people truly got to hear him more, had he played on more programs listened to young people, who knows? Had this guy gotten that break, the kids would have absolutely gone crazy. He would have been one of the all-time music heroes. I mean that.”

— Simon Phillips

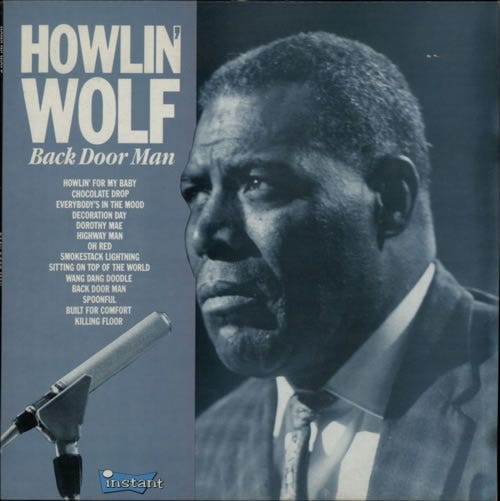

As it was, Wolf wrote and recorded songs for Chess that became blues standards: “Smokestack Lightning,” “Killing Floor,” and many others. Chess songwriter Willie Dixon also wrote classic blues songs for Wolf such as “Spoonful,” “Little Red Rooster,” “Evil,” “Back Door Man,” and “I Ain’t Superstitious.”

“His blues could be savage, doleful, elated, or mournful by turns, depending on his mood, and the fascination of his performance, aside from the towering nature of the music itself, was his almost constant sense of engagement”.

— Peter Guralnick for Rolling Stone

The Wolf would go on to leave his imprint on the very fabric of music with his recordings on Chess and his performances with his trademark voice, appearance and style that would live on long after his death.

During the 1960s, Wolf and Hubert continued to record sizzling blues that anticipated blues-rock — classic songs such as “Commit a Crime,” “Hidden Charms,” and “Love Me, Darlin’” In 1964, he toured Europe, including the U.K. and even Eastern Europe, with the American Blues Festival.

In 1965, he appeared on the American television show “Shindig” with the Rolling Stones. In 1970 he recorded The London Howlin’ Wolf Sessions in England with Eric Clapton, members of the Rolling Stones, and other British rock stars. It was his best-selling album, reaching #79 on the pop charts.

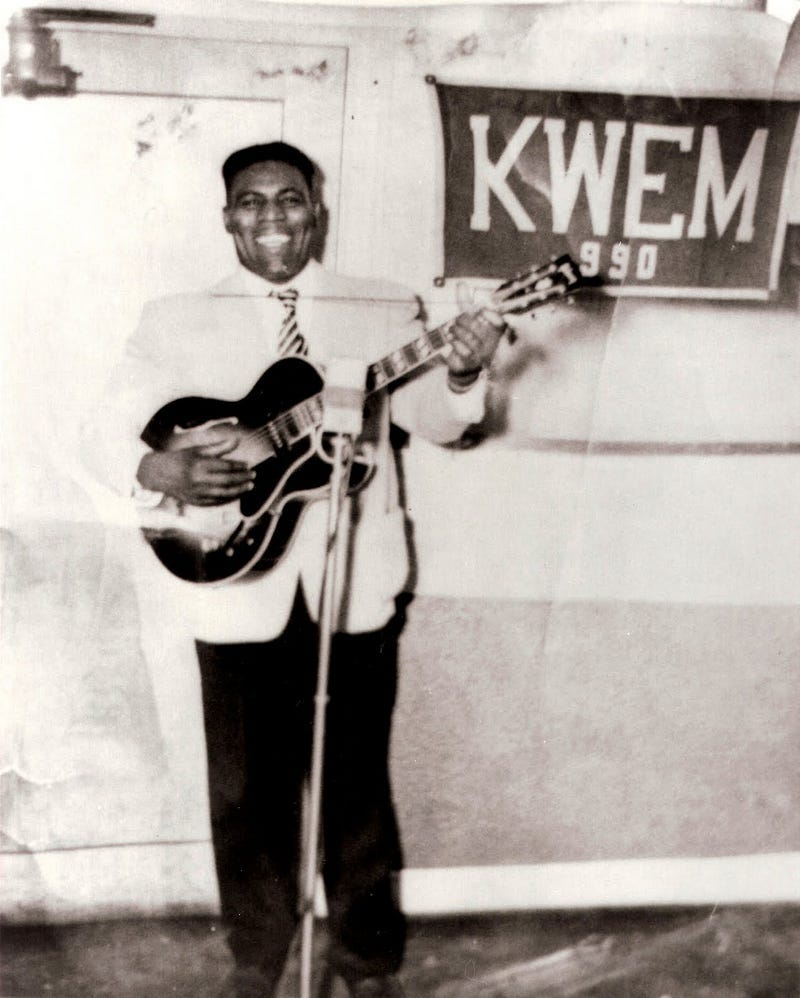

This was despite him being a 60-year-old man and also a very ill one. In the late 1960s and 1970s, Wolf suffered several heart attacks, and his kidneys began to fail him.

For the rest of his life, he received dialysis treatments every three days. Despite his failing health, Howlin’ Wolf stoically continued to record and perform.

In 1972 he recorded a live album at a Chicago club, “Live and Cookin’ at Alice’s Revisited.” In 1973, he cut his last studio album, “Back Door Wolf” which included the incendiary “Coon on the Moon,” the autobiographical “Moving,” and “Can’t Stay Here,” which harked back to Charley Patton.

Wolf’s last performance was in November 1975 at the Chicago Amphitheater. On a bill with B.B. King, Albert King, O. V. Wright, Luther Allison, and many other great bluesmen, Wolf gave a heroic performance, rising almost literally from his deathbed to recreate many of his old songs and performing some of his old antics such as crawling across the stage during the song “Crawling King Snake.”

The crowd went wild and gave him a five-minute standing ovation. When he got offstage, a team of paramedics where called in to revive him. Two months later he died in Chicago during an operation for a brain tumor. He was buried in Hines, IL.

Wolf was inducted into the Blues Foundation’s Hall of Fame in 1980 and the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1991.

In the years since his passing, his music remains well preserved and an essential listen for all blues and rock and roll fans and is testament to his genius, and he is now well remembered and revered as one of the most legendary blues musicians to have every lived.

There will never be another Howlin’ Wolf.

If you liked this post, you can buy me a cup of coffee by clicking the link below!